GM Sam Chin likes to say “if it’s a circle, it has a center. If it has a center it has four quarters.”

We tend to think of breathing as simply inhale and exhale, but I began to notice during my breathwork a year or so ago, one full breath cycle should also have four quarters.

Each inhale and exhale has two phases; an active phase and a passive phase separated by a neutral point.

The neutral point is when the diaphragm is completely relaxed and there is no movement of either inhale or exhale because the relative pressure inside the lungs matches the external pressure.

If we inhale from here, the inhale is active, requiring some effort from muscles like the external intercostals of the ribs, and if done properly the rib cage expands as the lungs fill with air. At the very top of the breath, we reach maximum pressure inside the lungs.

From here we can simply relax and the built-up pressure will cause the air to rush out of our lungs until we reach the neutral point again. This is the passive phase of the exhale. Below the neutral point, we can use some effort to continue to exhale actively, which should cause the waist and rib cage to continue to condense by activating muscles like the internal intercostals and transversus.

At the bottom of the active exhale, we’ve built up some negative pressure inside the lungs; if we simply relax, the vacuum will draw some air into the lungs until we reach neutral, and this is the passive phase of the inhale.

We need to acknowledge and actively train each of the four phases to some degree.

Why? Like anything else, it’s “use it or lose it” as we age.

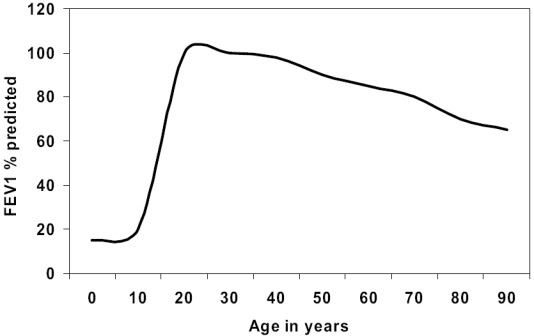

Lung function declines by almost 40% over the lifetime of an average individual, more so in men than women.

Most people develop a shallow, “vertical” breathing pattern that involves too much involvement of the neck and shoulders as their activity levels decline, spending most of their time breathing at and just above the neutral point.

This lack of excursion (change in diameter) causes ossification in the rib cage. As the rib cage becomes increasingly stiff, we’re forced to take more breaths to maintain our normal 5-6L of air per minute. Heart rate and sympathetic (fight or flight) nervous system activation are directly linked to our diaphragm, this increased number of breaths per minute shifts us into mild chronic physiological stress.

The alveoli, the tiny sacs in our lungs where O2/CO2 are exchanged, become deflated and increase dead airspace within the lungs reducing our ability to take in fresh oxygen.

Respiratory muscle strength decreases with disuse, impairing effective airway clearance leaving us prone to infection.

We’re also left with less and less reserve to meet our needs during high demand states like when we’re fighting off a bear (or pneumonia).

Pulmonary (lung) function measured as a function of forced expiratory volume has been shown to be a reliable indicator of life expectancy.

We also have research that shows that breathwork can and does improve lung function in older adults, so if your over 50 and you haven’t been doing breathwork your whole life, you don’t need to throw in the towel.

Start today and do what you can, with what you have where you’re at.

Here’s what to do

- become more mindful of your breathing all the time. Make sure you’re spending time breathing in all four quarters throughout the day.

- incorporate max inhales and exhales during your breathwork. Reach both hands above your head, inhale to your max and try to flare your ribs as wide as possible like the hood of a cobra

- Ball your hands into fists and pull arms down close to your sides and exhale as much as possible. Feel your rib cage and waist get as small as possible. Repeat 10x. (bonus, if you’re training a martial art like I Liq Chuan, when you fajin, you’re already training your forced expiratory volume!)