Brain Over Body – Inner Workings of The Inner Fire

I’ve been training in adaptation to both hot and cold for several years (each one has particular benefits to health, and performance), but it wasn’t until this past October that I attended a formal workshop on the material with the Art of Breath coach Rob Wilson. Although I had done Wim Hof’s 10 Week Course, I wasn’t completely happy with it. I felt that there were “secrets” missing from the material, some of which I uncovered by accident, in Scott Carney’s book “What Doesn’t Kill Us”.

The workshop with Rob Wilson was a good experience on many levels, the most important of which was just validating my experience with training cold exposure up to now, and also helped clarify my experience with the Wim Hof online course; compared to deep meditation methods like Vipassana or Zen which are meant to completely overhaul your mental “operating system”, cold exposure practice is really so simple, there’s not much “how to” to talk about, just do it, and nature pretty much handles the rest over time. The keys are a little bit of intent, and controlling your breathing to manage your physiological state.

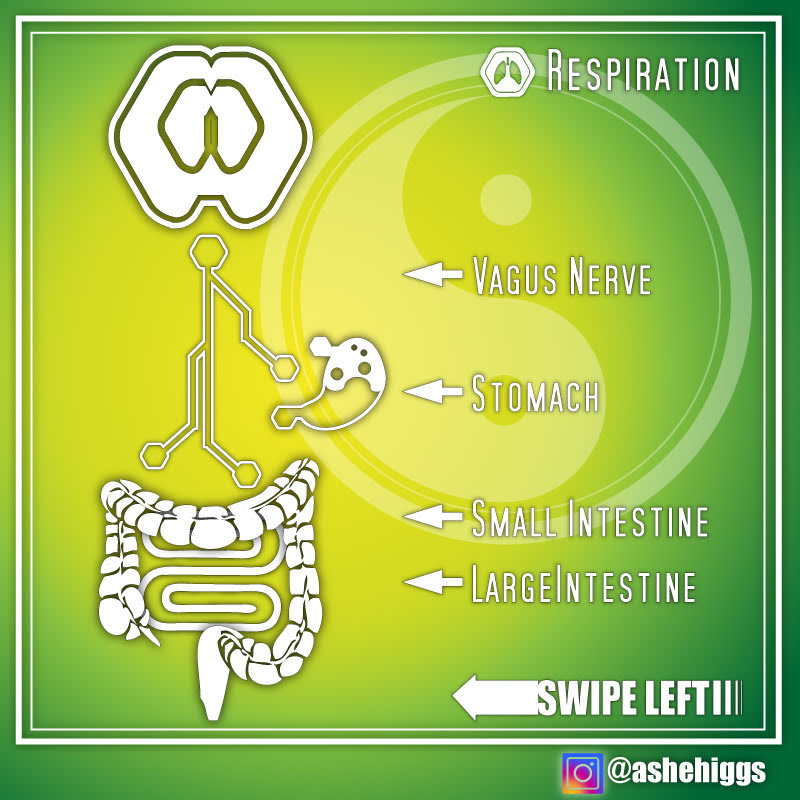

Recently I posted about a review paper that detailed some of the relationships between breathing exercises and improvements in immune function and now, we have some more exciting new findings in regards to respiration / breathing exercises and cold exposure from Wayne State University as part of exerting active control over normally autonomic functions in the body. The study is titled “Brain over body”–A study on the willful regulation of autonomic function during cold exposure Here are a few highlights from the study

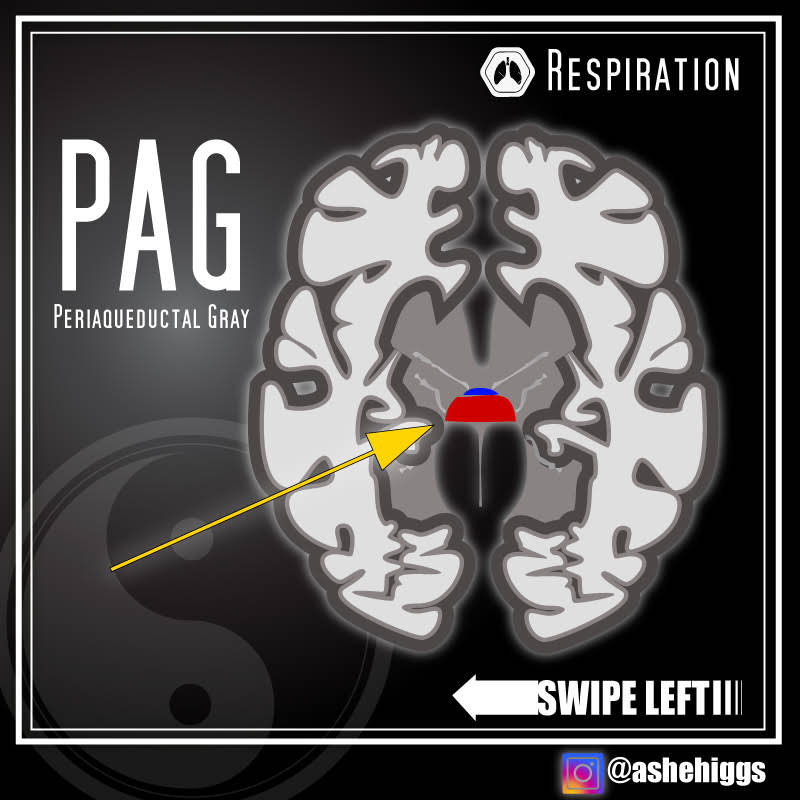

- fMRI analyses indicated that the WHM activates primary control centers for descending pain/cold stimuli modulation in the periaqueductal gray (PAG)

- The periaqueductal gray (PAG), also known as the central gray, constitutes a cell dense region surrounding the midbrain aqueduct.

- In addition, the WHM also engages higher-order cortical areas (left anterior and right middle insula) that are uniquely associated with self-reflection, and which facilitate both internal focus and sustained attention in the presence of averse (e.g. cold) external stimuli.

I think one of the more interesting findings from the study was that BAT, or brown fat, played a negligible role in generating heat to maintain core temperature during cold exposure, but instead the muscles of the rib cage, the intercostals, played the chief role by burning massive amounts of glucose.

This helps add some understanding to my own experience with the practice, which is that anytime I’m sleep deprived, or in a fasted state I have a much more difficult time resisting the cold compared to when I’m fed, and rested.

I commonly fast two days a week, and the first three or four days of every month. In a fasted state, core temp drops a bit anyway, and my system may not yet be fat adapted well enough to efficiently keep up with the higher demand for blood sugar through gluconeogenesis. (I suspect this is true, as I still have not recovered 100% of my exercise performance since switching to a ketogenic diet in June of this year). There was also a recent study done that showed blood ketone levels above 2.0 (which wouldn’t be uncommon during fasting) basically results in “ketone resistance”.

Similarly, cortisol levels are high, and you’re naturally more insulin resistant when sleep deprived, so again, this could potentially play a role in not being able to keep up with the glucose demands of the “inner fire” practice.

If you’d like a nice animated synopsis of the study and the results, the official Wim Hof YouTube channel released a nice video about it.

Complete coaching for MIND & BODY.

● Nutrition ● Mindfulness ● Martial Arts ●

Staying strong over 40. Sign up for my FREE newsletter👇👇👇 (http://bit.ly/2sGor97) Classes held in Tempe, AZ and workshops worldwide.

References 1. “Brain over body”–A study on the willful regulation of autonomic function during cold exposure

Author links open overlay panelOttoMuzik

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811918300673?via%3Dihub